TC Palm Columnist Ed Killer discusses the recent fish kill in Banana Lagoon and its long-term impact with Zack Jud, Director of Education at Florida Oceonographic Society: Ed Killer

The photos of acres of dead rotting fish on Facebook timelines have generated public outcry. But how can this fish kill in the Banana River Lagoon, a prong of the Indian River Lagoon in central Brevard County, be properly quantified in terms of its impact on an estuary?

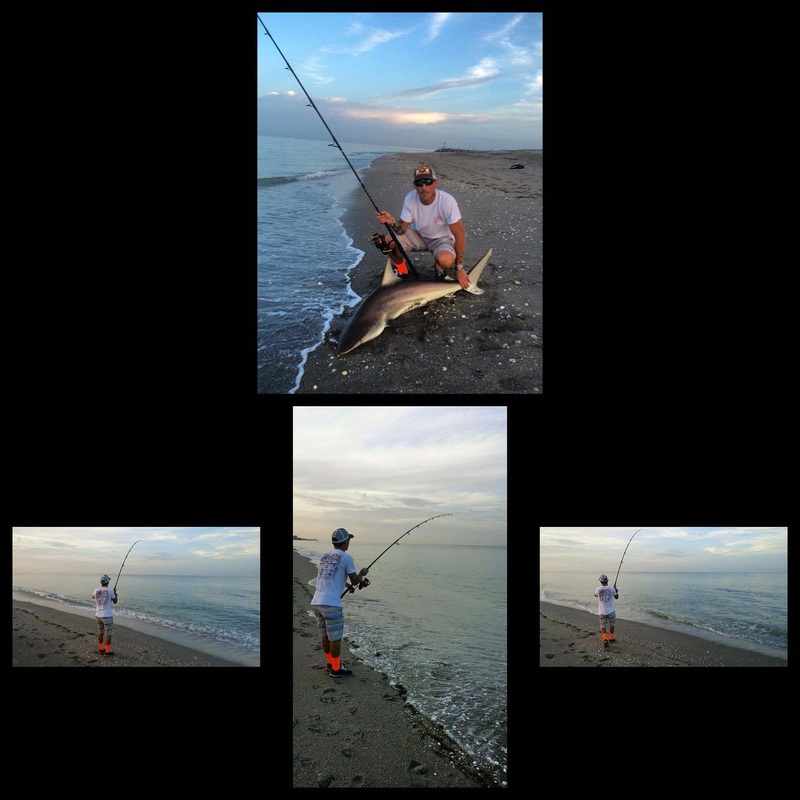

I asked Zack Jud to help me explain it. He's the director of education for Florida Oceanographic Society based in Stuart. But he's also a devoted light tackle angler, marine fishery scientist and associate scientist for the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust.

Jud is saddened by what is happening in a part of the Indian River Lagoon just a few miles north of the Treasure Coast.

He said the shallow water sport fishing of the Space Coast could be negatively impacted for years, but biologically speaking, it could be worse than that.

"It petrifies me that we may have lost the entire breeding stock of redfish in the Banana River," said Jud.

When he is working at his desk, he is reminded of how special an area that is for fishing. Like a lot of anglers, his computer screen saver features a rotating set of images of memorable catches. Redfish weighing over 25 pounds. Black drum even bigger. Trout as long as his arm.

Many were caught on fly fishing tackle, which he prefers to bait fishing. Many were caught in the same Banana River now is awash in dead fish from shoreline to shoreline.

What happened?

Jud tried his best to explain in plain language the sequence of events that led to the massive fish kill. There already was a presence of a high population of algae in the waters there. Experts were referring to it as a "brown tide," and it was being documented by researchers as long ago as November.

Then something triggered a near total die-off of the algae — something scientists don't fully understand yet — like rain, or cloud cover, or rapid temperature change. Bacteria began immediately consuming the algae. That process uses up all the available dissolved oxygen in the water. Fish need dissolved oxygen to live.

No oxygen means no life.

What caused this to collapse in the first place? That's another column. But Jud said its ramifications are especially catastrophic in this particular location.

"The Banana River has one of the most unique populations of redfish in the world," Jud said. "Redfish there have evolved to live their entire life cycle inside the lagoon. Everywhere else, pretty much, redfish spend their adult lives offshore or at least spawn there, like the big redfish at Sebastian Inlet.

"In the Banana River, redfish go from spawn to egg to larvae to juvenile to adult all in the same estuary, which is unusual."

The question is, and the answer won't be known for months possibly, how much of that population has been wiped out? All of it? A small percentage?

Jud said it's hard to know at this point.

Trickle down

"Unfortunately," Jud said, "no one gives a (darn) about the environmental impacts of a fish kill. But this one has economic impacts, too."

He spoke with Capt. Rick Worman, a guide who uses the Banana River as his office, and he already has lost thousands of dollars in canceled charters this week. But Worman's lost wages don't stop there. Those same anglers won't rent cars on the Space Coast, won't book airline tickets, won't stay in hotels, won't eat at restaurants and won't spend other money locally. They'll go somewhere else. Maybe they'll head to Costa Rica, where there is an epic sailfish bite, or out west to fly fish a stream for trout.

The same thing also is happening in Stuart, Fort Myers, Punta Gorda and the Upper Florida Keys, where Florida Bay is in the midst of a collapse similar to the one in the Banana River. And those aren't the only troubled waters in the state.

"Bonefish simply are not anywhere along the west shorelines of Biscayne Bay for some reason," Jud explained. "The shrimp, rays and other fish are there, but the 8- to 12-pound bonefish anglers could sight cast to aren't there."

The problem is so severe, the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust announced last week it has entered into an agreement with Florida Atlantic University's Harbor Branch to raise bonefish in captivity to release into the wild.

The same cannot happen with the redfish, Jud said.

"The state has a redfish hatchery at Port Manatee (near Bradenton), but by law it cannot move those fish elsewhere unless the brood stock has been caught in those waters," he said. "That means the state would have to have brood stock from Banana River if that was to happen."

But the water problems have to be fixed first.

"We're seeing water issues being handled improperly statewide because our state government does not value the health of our ecosystems," he said.

The proof is floating atop the waves of the Banana River Lagoon right now.

Watch a few videos for more info

RSS Feed

RSS Feed